On the way into work, Clayton Ruley passes several people who use drugs propped up against buildings and dozing off on one another’s shoulders. Since 2008, using the drug naloxone, commonly known as Narcan, he has rescued 60 people from dying of overdoses.

Story by Melissa Dribben

Photos courtesy of Clayon Ruley

Ruley, 40, is the director of community engagement and volunteer services for Prevention Point, a life-saving nonprofit for people who use drugs in the city.

In 2017, more than 70,200 Americans died from drug overdoses, and more than 1,200 of those deaths were in Philadelphia.

Half of those deaths occurred in Kensington, the neighborhood where Prevention Point is located.

Most people here carry Narcan and know how to use it, Ruley says. “These are their trenches.” But he thinks everyone – everyone – should carry the medication and be trained in how to reverse an overdose.

“Opioids and drugs do not discriminate,” he explains, a fact that has become increasingly obvious as the crisis has spread. “Opioid overdoses are killing people everywhere from board rooms to college campuses.”

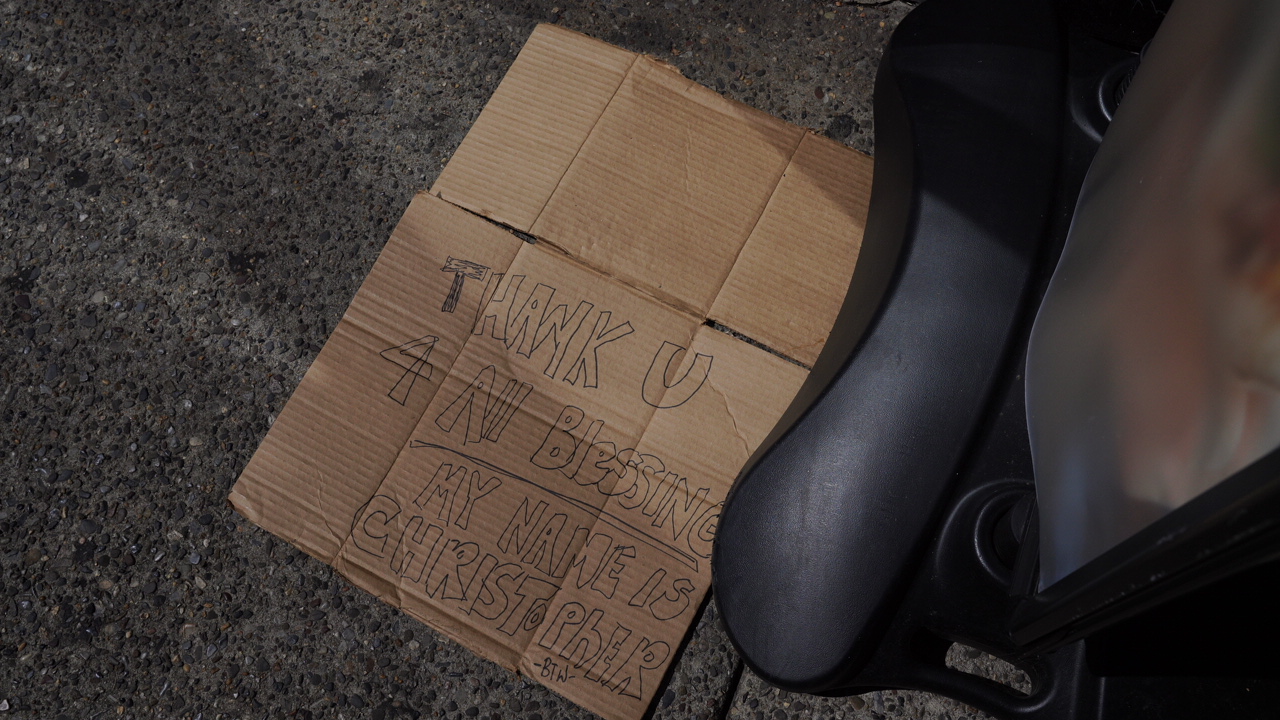

As the nexus of the city’s drug trade, Kensington has been the focus of numerous news reports and government intervention. Critics have complained that not enough attention has been given to the many hard-working families who live there, or to the humanity of those struggling with drug addiction.

Within a block of Prevention Point on a recent afternoon, several parents kept a watchful eye on children riding tricycles up and down the sidewalks. Men huddled shoulder to shoulder, working under the hoods of cars in need of engine repair. Blooming cherry trees flaunted their new pink regalia.

But there is no denying the shadow the opioid has cast on this area.

When a particularly powerful shipment of Fentanyl made its way into the drug supplies several months ago, more than 20 people overdosed in one day and were given Narcan at Prevention Point. The agency’s safe injection kits now include a Fentanyl test strip.

“When it’s positive,” he says, “At least they know before they fly.“

Few among the nearly 100 employees and dozens of volunteers at Prevention Point expect the crisis to subside anytime soon, says Ruley, who has worked for Prevention Point since 2010 when he was hired as an intern during graduate school at Bryn Mawr College.

Back then, the agency had already been around for two decades. It began as an underground grassroots needle exchange program and has expanded to provide a comprehensive range of services, including medical care, counseling, legal aid, meals, clothing, housing, and training in how to use Narcan to save someone who has overdosed on opioids.

In April, Ruley stepped into a new job, focused on spreading the word about the agency’s services and enlisting parent groups, store owners, city agencies and civic associations to join the effort to save lives with Narcan.

He came to this work organically. Both his parents were social workers and imbued in him a dedication to community service, he said. After graduating from West Philadelphia High School, where he played football and baseball, threw shotput for field and track, and sang baritone in the choir, he studied communications at Bloomsburg University and ran an on-line magazine for awhile. But it wasn’t long before he gravitated towards social service work.

While he continues to multi-task at Prevention Point, in his new role he is more focused on public education.

Recently, he was invited to speak to the Chestnut Hill Rotary Club, where he answered gently challenging questions about the opioid epidemic and Prevention Point’s work.

“Why does Philadelphia have such a big drug problem?”

“Do you educate people about personal responsibility?”

“When you work with sex workers, do you try to train them for a different industry?”

He answered each one in his calm, gentle baritone, recounting the history of the crack epidemic, job loss, homelessness, the racial and socio-economic imbalance in criminal prosecution and its destabilizing effect on families and communities.

“If the objective was to fill prisons with non-violent people, it was a success,” he said. “It certainly didn’t stop drugs.”

Browbeating someone into beating an addiction simply does not work, he explained. So he and his colleagues work on harm reduction, their shorthand for treating and preventing the spread of diseases like HIV and hepatitis and helping drug users survive.

“When you have the motivational moment to make a change, nothing is going to stop you,” he said. “But rehabilitation is really about relapse. People have to be alive to be in recovery.”

The Rotarians’ questions, Ruley said, were a far cry from the hostile ones he has fielded in other forums. But whether bluntly or subtly, wherever he goes, Ruley said he is asked to explain why precious public funds and personnel and valuable volunteer efforts should be invested in people who repeatedly engage in life-threatening behavior.

Over the past few years, as the epidemic has spread to middle and upper-middle class communities, he said people are less apt to try to distance themselves.

No longer are they as likely to characterize addiction as the self-inflicted consequence of weak resolve and poor upbringing.

After accepting offers of donations and support from the Rotary, he made his way back to Prevention Point.

Housed in a 23,000 square-foot former church with candy pink stained glass crosses in the doors, the agency is open – and crowded – seven days a week.

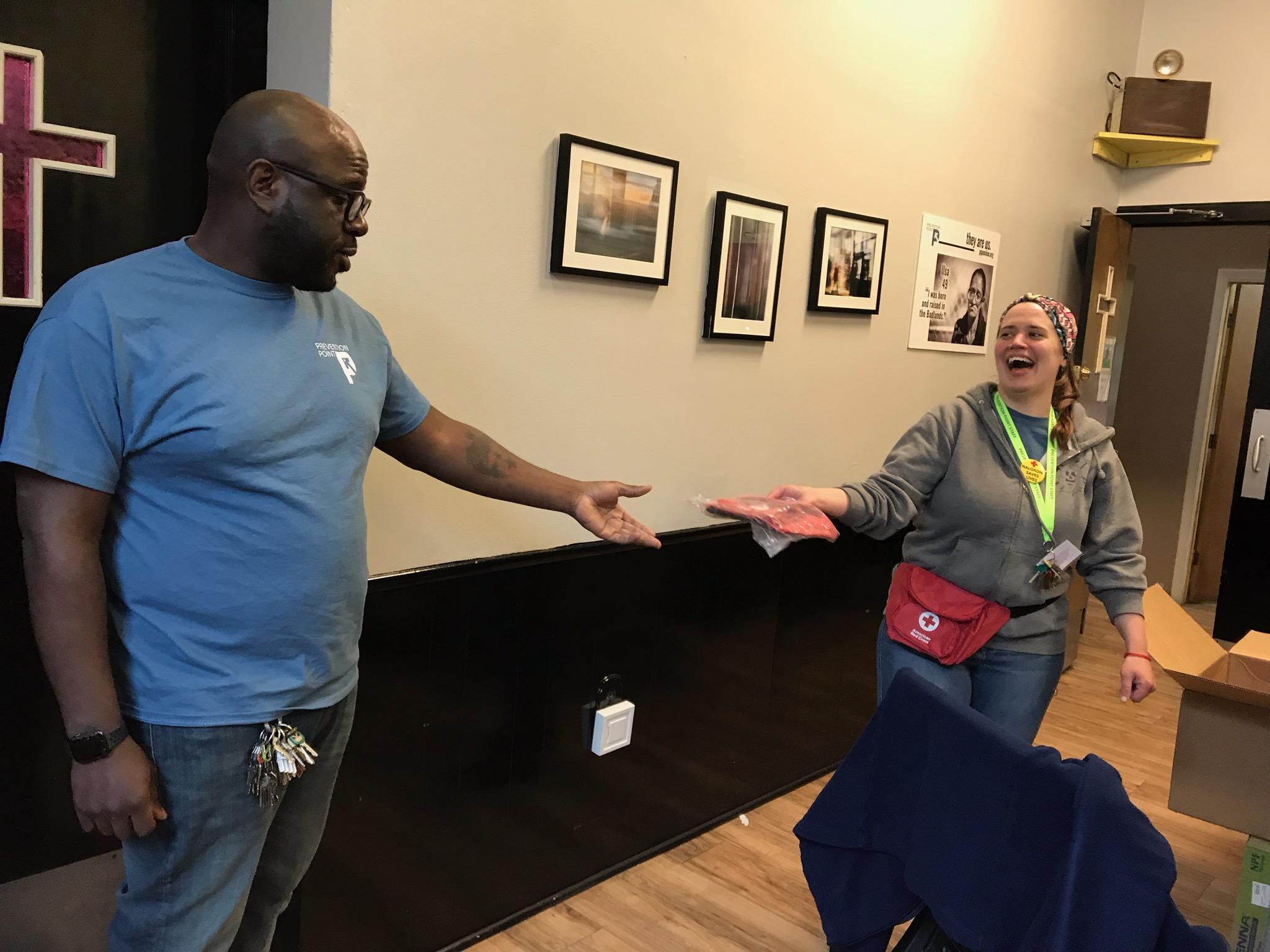

He passes one of the staff physicians, a slight man in a bow tie, who holds a master’s in public health. Several medical students who have volunteered to organize medications for HIV and hepatitis. He accepts one of the newly delivered red fanny packs for Narcan kits being distributed by a co-worker in charge of overdose prevention and harm reduction.

Ruley cannot remember the first time he reversed an overdose, but from the beginning, he discovered that he was extremely calm under the pressure.

“You are in the moment. Time slows down. Your senses are heightened. You think about the steps and who is around to help,” he says, and proceeds to outline the relatively simple protocol that he and his co-workers have now taught to the thousands of people they have trained to use Narcan.

He unzips a small blue nylon sack and lays out the contents. Sterile gloves. A plastic sheet to be used as a sanitary barrier when applying mouth to mouth resuscitation. And the medicine in a white plastic package resembling something between an antihistamine nasal spray and a dental floss container.

First, he says, you assess the responsiveness of the person you think has overdosed. Is their skin gray or blue? Are they breathing? Snap your fingers, press on their nail beds, shout, “Hey! Hey!” or push your knuckle up against their nose bone. If there is no murmur, blink or flinch, call 911 and get to work.

Clear the person’s airway. Spray the medicine into one of their nostrils, and while you are waiting for it to take effect, breathe for them.

“It’s a lot of responsibility,” Ruley says. “But so is someone dying on your doorstep.”

The feeling he gets watching someone come around, seeing the color return to their face and their eyes flutter open is hard to describe, he says. “It’s a combination of rush and relief. You are happy that it’s over, but you’re waiting to not have to do this that often.”